The most common reasons for a trademark application to be rejected are lack of distinctiveness or prior registered trademarks. In addition, there are many other possible grounds for a trademark application to be refused. One of these grounds is that the trademark is contrary to public policy or against accepted principles of morality.

This rule (in one way or the other) exists in almost all countries. The European Union Intellectual Office (EUIPO) is very strict in applying this rule.

As a preliminary comment, the rule preventing trademarks that are against public policy or immoral does not in itself preclude companies from using such marks. It simply means that companies cannot get exclusive rights to them. It is entirely possible that a mark is rejected on being contrary to principles of morality, but there is no problem in using the mark

The rationale behind the rule is that the EUIPO does not want to assist or encourage people who wish to further their business aims with trademarks that offend other people.

So, the first point to note is that you cannot get exclusive rights to offensive marks. As said, this in itself does not mean that you cannot use such marks. There might be other laws that an offensive trademark might violate (for example, it could incite racial hatred).

What kind of marks get flagged?

It is relatively rare that a trademark is refused for being contrary to “public policy”. This would be the case where the trademark is contrary to political and social order and universal values of human dignity, freedom, equality, democracy, and the rule of law. For example, a trademark application containing a Nazi swastika would be flagged under this rule, as well as trademarks referring to terrorism. Also, trademarks attempting to justify, glorify, support, or trivialize the Russian aggression against Ukraine have been refused on these grounds.

It is slightly more common for trademarks to be refused for being immoral (contrary to principles of morality) than for being against public policy. Immoral trademarks refer to marks that are considered blasphemous, racist, discriminatory, or insulting by a reasonable consumer with average sensitivity and tolerance. Trademarks that are simply of bad taste are not flagged or objected on this ground.

So what does that mean in practice? How is this rule applied? Here are some examples of refused trademarks.

SCREW YOU. The EUIPO refused this trademark because it considered it a profanity despite acknowledging that it was not the coarsest possible term. The EUIPO thought that people in Britain and Ireland would be upset by commercial exposure to the term. The UK trademark office did not find the mark particularly offensive and accepted its registration.

PAKI. The European Court refused to register the trademark PAKI because it was considered a racist, derogatory and insulting word for Pakistani people.

The second one is clearly racist whereas the first one seems quite mild. Expression “Screw You” may be insulting and even bad taste, at least to some, but on the other hand, it seems a bit excessive that it was considered to be such profanity that it is refused protection.

The EUIPO has also refused many trademarks on very flimsy grounds, almost to the point of ridiculousness. At first, they refused to register the trademark COPYCAT for cosmetics and leather products because it was thought to be suggestive of illegal activity, namely counterfeiting. The decision was overturned at a higher instance (Board of Appeal) and COPYCAT was allowed to be registered. Not so lucky was the owner of trademark application KNOCKOFF that was also refused because it was viewed to refer to counterfeiting or the owner of the trademark PIK-A-POO for “Scoops for the disposal of pet waste.” If anything, the mark “PIK-A-POO” could be refused because it directly describes the product, but certainly not because it’s too offensive.

These examples show that the threshold for a mark to be considered immoral is sometimes almost comically low.

So what kind of marks are in trouble?

There are three clear categories that get particularly turbulent treatment. These are marks that refer to a) sex, b) drugs and c) mafia/crime.

Here are examples of refused trademarks from each category

Sex

TOUCH MY HOLE

PINK PUSSY (logo)

FIFTY SHADES OF FUCKED UP

Drugs

CBDwater (logo)

CANNABIS STORE AMSTERDAM (logo)

CANNABIS

VAPZ HASH STIX

Mafia

MAFIA

SK8MAFIA

MAFIA RAVE

ESPRESSO MAFIA

BOSS OF MAFIA

Trademarks that refer to criminals, terrorists, and atrocities have also been rejected. These include applications for HITLER, BIN LADIN, and MH17. Religion is a sensitive issue as well. The EUIPO refused to register the trademark SWEET JESUS. The applicant sought to register both a word mark and a logo mark. The logo version did not probably get many extra points from the examiners:

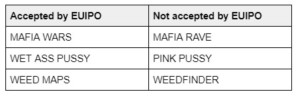

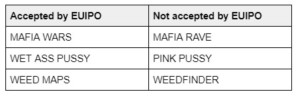

On the other hand, the EUIPO has accepted many trademarks that appear very similar in terms of their objectionability to the ones mentioned above.

Here are some examples:

All languages matter

One thing that applicants must also bear in mind is that EU trademarks are examined in all EU languages. This applies equally to the possible descriptiveness of the mark and its possible immorality. This may cause surprises.

In 2014 the Irish Cattle Breeding Federation sought to register the trademark EBI. They had used the mark EBI as an abbreviation for “European Breeding Index” and wanted to trademark it. The EUIPO refused to register the mark because it means “Fuck” in Bulgarian. So if the mark has an offensive meaning in any EU language, it will be rejected.

Not everyone is equally sensitive

It is also possible that sensitivities vary across the EU. Some countries may be more secular than others, others are less sensitive to for example religious statements, and not all languages are understood across the EU. If the trademark has possibly immoral meaning in Danish, it should be assessed according to how an average Danish consumer views the mark, i.e. whether (s)he is offended by it.

Another departure from “normal” trademark rules is that immorality or objectionability is not assessed only with respect to the target group of the products in question. For example, in assessing the distinctiveness of a trademark, it is always done in relation to how the target group of that product perceives the mark (for example, would a pet owner consider a particular pet food name to be descriptive?). With immoral marks, the examination is not limited to the users of the products and services. This is because also other consumers may be exposed to the mark.

The challenge for assessing immoral and offensive marks stems from the fact that there are 27 member states with different cultures and ideas of what is offensive and immoral. The same applies to EUIPO examiners, who come from various backgrounds. This inevitably leads to inconsistencies. As a consequence, it is often difficult to assess whether a mark is registrable or not.

Conclusion

Trademarks that are immoral or against public policy are not registrable in the EU. Applicants should be particularly cognizant of this if they have a brand that relates to sex, drugs or crime. EUIPO has shown to be highly restrictive in its practice and even very mild profanities have been refused on this grounds. On the other hand, EUIPO’s practice is very inconsistent. Sometimes very mild expressions get rejected, whereas sometimes quite vulgar expressions have been accepted.

Applicants will most likely get better and more consistent treatment in national trademark offices that are much more liberal in accepting these kinds of marks. Their marks can in most instances be registered at the national level, but having to file several national applications will inevitably lead to higher costs.

All languages matter

One thing that applicants must also bear in mind is that EU trademarks are examined in all EU languages. This applies equally to the possible descriptiveness of the mark and its possible immorality. This may cause surprises.

In 2014 the Irish Cattle Breeding Federation sought to register the trademark EBI. They had used the mark EBI as an abbreviation for “European Breeding Index” and wanted to trademark it. The EUIPO refused to register the mark because it means “Fuck” in Bulgarian. So if the mark has an offensive meaning in any EU language, it will be rejected.

Not everyone is equally sensitive

It is also possible that sensitivities vary across the EU. Some countries may be more secular than others, others are less sensitive to for example religious statements, and not all languages are understood across the EU. If the trademark has possibly immoral meaning in Danish, it should be assessed according to how an average Danish consumer views the mark, i.e. whether (s)he is offended by it.

Another departure from “normal” trademark rules is that immorality or objectionability is not assessed only with respect to the target group of the products in question. For example, in assessing the distinctiveness of a trademark, it is always done in relation to how the target group of that product perceives the mark (for example, would a pet owner consider a particular pet food name to be descriptive?). With immoral marks, the examination is not limited to the users of the products and services. This is because also other consumers may be exposed to the mark.

The challenge for assessing immoral and offensive marks stems from the fact that there are 27 member states with different cultures and ideas of what is offensive and immoral. The same applies to EUIPO examiners, who come from various backgrounds. This inevitably leads to inconsistencies. As a consequence, it is often difficult to assess whether a mark is registrable or not.

Conclusion

Trademarks that are immoral or against public policy are not registrable in the EU. Applicants should be particularly cognizant of this if they have a brand that relates to sex, drugs or crime. EUIPO has shown to be highly restrictive in its practice and even very mild profanities have been refused on this grounds. On the other hand, EUIPO’s practice is very inconsistent. Sometimes very mild expressions get rejected, whereas sometimes quite vulgar expressions have been accepted.

Applicants will most likely get better and more consistent treatment in national trademark offices that are much more liberal in accepting these kinds of marks. Their marks can in most instances be registered at the national level, but having to file several national applications will inevitably lead to higher costs.

All languages matter

One thing that applicants must also bear in mind is that EU trademarks are examined in all EU languages. This applies equally to the possible descriptiveness of the mark and its possible immorality. This may cause surprises.

In 2014 the Irish Cattle Breeding Federation sought to register the trademark EBI. They had used the mark EBI as an abbreviation for “European Breeding Index” and wanted to trademark it. The EUIPO refused to register the mark because it means “Fuck” in Bulgarian. So if the mark has an offensive meaning in any EU language, it will be rejected.

Not everyone is equally sensitive

It is also possible that sensitivities vary across the EU. Some countries may be more secular than others, others are less sensitive to for example religious statements, and not all languages are understood across the EU. If the trademark has possibly immoral meaning in Danish, it should be assessed according to how an average Danish consumer views the mark, i.e. whether (s)he is offended by it.

Another departure from “normal” trademark rules is that immorality or objectionability is not assessed only with respect to the target group of the products in question. For example, in assessing the distinctiveness of a trademark, it is always done in relation to how the target group of that product perceives the mark (for example, would a pet owner consider a particular pet food name to be descriptive?). With immoral marks, the examination is not limited to the users of the products and services. This is because also other consumers may be exposed to the mark.

The challenge for assessing immoral and offensive marks stems from the fact that there are 27 member states with different cultures and ideas of what is offensive and immoral. The same applies to EUIPO examiners, who come from various backgrounds. This inevitably leads to inconsistencies. As a consequence, it is often difficult to assess whether a mark is registrable or not.

Conclusion

Trademarks that are immoral or against public policy are not registrable in the EU. Applicants should be particularly cognizant of this if they have a brand that relates to sex, drugs or crime. EUIPO has shown to be highly restrictive in its practice and even very mild profanities have been refused on this grounds. On the other hand, EUIPO’s practice is very inconsistent. Sometimes very mild expressions get rejected, whereas sometimes quite vulgar expressions have been accepted.

Applicants will most likely get better and more consistent treatment in national trademark offices that are much more liberal in accepting these kinds of marks. Their marks can in most instances be registered at the national level, but having to file several national applications will inevitably lead to higher costs.

All languages matter

One thing that applicants must also bear in mind is that EU trademarks are examined in all EU languages. This applies equally to the possible descriptiveness of the mark and its possible immorality. This may cause surprises.

In 2014 the Irish Cattle Breeding Federation sought to register the trademark EBI. They had used the mark EBI as an abbreviation for “European Breeding Index” and wanted to trademark it. The EUIPO refused to register the mark because it means “Fuck” in Bulgarian. So if the mark has an offensive meaning in any EU language, it will be rejected.

Not everyone is equally sensitive

It is also possible that sensitivities vary across the EU. Some countries may be more secular than others, others are less sensitive to for example religious statements, and not all languages are understood across the EU. If the trademark has possibly immoral meaning in Danish, it should be assessed according to how an average Danish consumer views the mark, i.e. whether (s)he is offended by it.

Another departure from “normal” trademark rules is that immorality or objectionability is not assessed only with respect to the target group of the products in question. For example, in assessing the distinctiveness of a trademark, it is always done in relation to how the target group of that product perceives the mark (for example, would a pet owner consider a particular pet food name to be descriptive?). With immoral marks, the examination is not limited to the users of the products and services. This is because also other consumers may be exposed to the mark.

The challenge for assessing immoral and offensive marks stems from the fact that there are 27 member states with different cultures and ideas of what is offensive and immoral. The same applies to EUIPO examiners, who come from various backgrounds. This inevitably leads to inconsistencies. As a consequence, it is often difficult to assess whether a mark is registrable or not.

Conclusion

Trademarks that are immoral or against public policy are not registrable in the EU. Applicants should be particularly cognizant of this if they have a brand that relates to sex, drugs or crime. EUIPO has shown to be highly restrictive in its practice and even very mild profanities have been refused on this grounds. On the other hand, EUIPO’s practice is very inconsistent. Sometimes very mild expressions get rejected, whereas sometimes quite vulgar expressions have been accepted.

Applicants will most likely get better and more consistent treatment in national trademark offices that are much more liberal in accepting these kinds of marks. Their marks can in most instances be registered at the national level, but having to file several national applications will inevitably lead to higher costs.