In today’s digital age, personal brands are becoming increasingly important. From social media influencers to celebrities, the way they talk or present themselves to the world can have a big impact on their fame, success, and recognition. But what about the most recognisable part of their personal brand – their face? Can it get trademark protection? The answer is surprisingly unclear.

Trademark law is a great tool for protecting various aspects of brands that are based on real people and personalities. In fact, many of the world’s biggest brands are based on people, like Gucci, Kellogg’s, McDonald’s, and Ford.

Here are some examples of how their brands can be protected:

Name: Gucci (EU trademark No. 000121988)

Signature:  (EU trademark No. 004853545)

(EU trademark No. 004853545)

Celebration:  (EU trademark No. 017157355)

(EU trademark No. 017157355)

Nick name or abbreviation: CR7 (EU trademark No. 015359094)

Catch phrase: Let’s get ready to rumble (International trademark No. 1679318)

While these are perhaps obvious ways to protect a celebrity’s brand, the often most recognisable aspect is missing: the facial appearance of the celebrity. If a name can be a trademark (as it obviously can), how about a face?

In 2017 a Dutch model Maartje Verhoef applied for a trademark consisting of a photograph of her face. The application was originally rejected on the grounds that it was a banal true-to-life representation of a face of a woman, and that it would not be perceived to indicate the commercial source of the products the application covered. The application was also partly rejected for being descriptive, on the basis that the image represented the category of whom the products were intended, namely women. It was also stated that the heads of women are commonly portrayed in various products, and they are not considered indicators of the commercial source. In other words, images of faces are perceived as merely ornamental.

The EUIPO’s Board of Appeal reversed the decision saying the following: “A photo of a person’s face, in the form of a passport photo, is a unique representation of that person, including his/her specific external features. Besides elements including a person’s first name and last name, a depiction of a person’s face in the form of a passport photo serves to identify that person and therefore to distinguish him/her from others”.

The EUIPO’s Board of Appeal has also accepted the portraits of models Yasmin Wijnaldum and Rozanne Verduin as trademarks. These were also first rejected by the examiners of EUIPO. This seems to end the matter.

While the Board of Appeal has accepted portraits of people as distinctive trademarks, later EUIPO practice makes things much more complicated. This is surprising because the examiners of EUIPO are supposed to follow the practice of the Board of Appeal.

In a string of recent decisions showing an image of famous persons, the EUIPO has held that there are many relevant considerations when examining the distinctiveness of a portrait:

- category of goods and services. It may be that for certain goods facial images can be perceived as more distinctive than for others. This is because buying habits vary across different types of products, the awareness of the relevant target group can be different, and in some products images of faces are used descriptively as ornaments.

- uniqueness and distinctiveness are different concepts. Even if every face is unique, it does not mean that this makes them distinctive. Recognizing two faces as different is not the same as distinguishing them by their different commercial origin.

- the face of a person must have gained fame in order to be seen as a trademark. Otherwise, it’s just a “face in the crowd” without any origin-indicating function.

- there may be a descriptiveness problem. A photo of a famous person in relation to, for example, books, will be perceived as indicating that the book is about that famous person.

These contrary decisions and viewpoints make it difficult to know what EUIPO’s current stand is. The examiners seem hesitant to the idea of registering faces as trademarks, while the Board of Appeal is more open to them.

Some of the points raised by EUIPO’s examiners are clearly valid considerations. It may be that for certain types of products faces are perceived as indicators of origin more than for other types of products. For example, it is perhaps reasonable to think that a woman’s head in a hair dye package is not particularly distinctive because almost every hair dye package seems to contain a portrait of a woman. The face serves to demonstrate the colour of the dye. It is less clear how the fame of the person seeking to protect the portrait impacts the distinctiveness. The EUIPO has considered fame to be a precondition for distinctiveness, but at the same time sees it as a problem because using the face of a famous person may at least for some products (like books) make the trademark descriptive.

Additional things to consider

If faces are accepted as trademarks, how should they be assessed against each other? In other words, when are two portraits “confusingly similar”? What is the criteria for this? How do, for example, race, ethnicity, age, and gender affect this assessment? What if the other person is famous, and the other is just a regular Joe. Will the fame of that one person make the two dissimilar?

According to the established principle, two trademarks (faces, in this case) are assessed bearing in mind the dominant and distinctive parts, taking into account that consumers cannot compare the marks (faces) side by side, but must rely on an imperfect recollection of the marks.

What would be the distinctive and dominant parts in a regular face? Of course, there could be faces that have truly distinctive features, like Frida Kahlo’s eyebrows or Albert Einstein’s hair. These would obviously be taken into account. Usually, people put the most focus on a person’s eyes, nose, mouth, ears, and hair. What about age, race, gender, ethnicity, etc? Is one of these aspects more dominant than the rest?

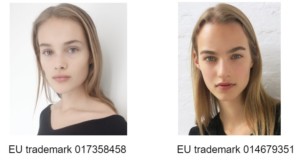

Would these two be similar trademarks?

These probably look quite similar even when compared side by side. The proper way to compare them is to assess them separately, with sufficient time lapse in between, so that there is only an “imperfect recollection” of the earlier mark.

Another issue to consider is that if the EUIPO requires some degree of fame for a face (portrait) to be sufficiently distinctive, the problem is that this fame must be established throughout the European Union, in other words, in every country. This makes it very difficult to protect a person’s face as a trademark for ordinary people and even for most celebrities. Only those who could establish fame in each EU country could benefit from this type of protection.

Conclusion

So, can you protect your face (image, portrait) as a trademark in Europe? The question is currently far from settled. While EUIPO’s examiners seem to be very apprehensive about this idea, the Board of Appeal is much more open to it. At some point, this question will end up in the Court of Justice of the European Union, and there will hopefully be an authoritative principle established as to whether it is possible, and if yes, what are the relevant considerations in assessing the distinctiveness of a face of a person, famous or otherwise.